Craftsmanship series interview by Natasha NawaTaNeko

Sitting through so many rope classes, observing many teachers in their flow teaching basic and advanced stuff and many beginners struggling to tie their first knot, to form the partners’ body in some sort of appealing position, to find more or lease sensible solution to tie off the the rest of the rope – I get to think a lot about Kinbaku as a craft based art. How we learn it and how we live it.

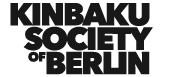

This reserach started with Spanish artist Laurent Martin “Lo” (Issue 7) I wanted to interview as I was so fascinated by the mobile bamboo structures. Talking with Laurent about his craft, I discovered many parallels with rope bondage. I wanted to know more and I kept looking for people who are good in what they do, who practice their craft for many years, but never seem to lose their passion.

I kept asking them pretty much the same questions about quality and how to recognize it, about tradition and creativity, about learning and sources of inspiration.

There were striking similarities in their answers.

It seems for many of them craft was not their decision, but first it “called” them. As Laurent Martin says: “When I started to slice, cut and tie (bamboo), I felt a very intimate relationship with it. It was an emotional, physical, sensual and spiritual encounter”.

Whilst the commitment was a big part of the process and it took all of them years to perfect their mastership through constant practice and repetition and “cutting their fingers”.

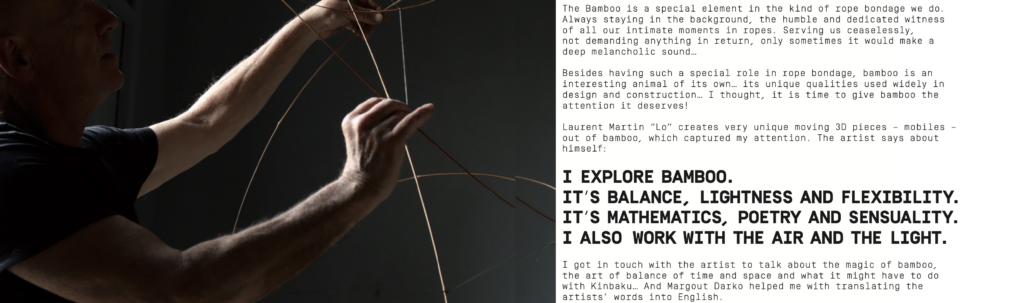

Senju Shunga (Issue 10): “To properly design full-body suits one has to throughly study Japanese history, religion and culture. The more I learned, the more intimate the relationship grew”.

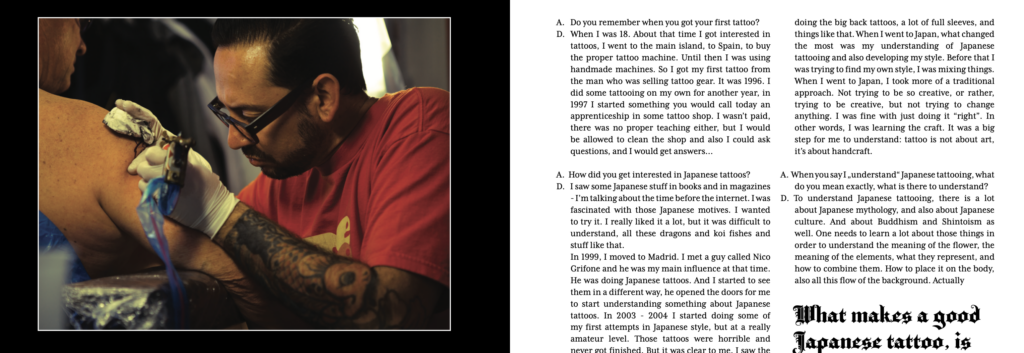

They all seem to have a great respect for the material they get to work with and its personality. Martin Lo said the bamboo cannot be told what to do, it cannot be molded without its agreement. The same way as Pawel Bolf (Issue 13) spoke about the steel he uses for his sword production or Dadan Horton (Issue 11), the Japanese inspired tattoo master, about the qualities of the skin.

The material you choose to work with, has a personality.

I guess this is where commitment plays a role: whether you are committed to this craft that has chosen you, whether you are committed to learn its personality and through that, to open its possibilities that are hidden for those who only get to know it superficially. Specialty is a key.

Pawel Bolf spoke about this in his interview: “each field in Japan is performed by a specialist. And even within a specialization, they often only produce products of certain styles or schools. That’s why the final product, a sword assembled from experty crafted parts, is so perfect… I’m a specialist in blades, and I also make very good sword guards. Polishing or accessories, I can do those at a decent-average level, but not pristine… My wife has been polishing for 10 years. She is getting pretty good at that”.

Cannot say it better. In crafts, it is through polishing tirelessly for 10 years, that you become better in polishing.

It always seems to be demanding on the body, to channel the craft, it is physical work. Chris Calvet (Issue 11) says, when he practices his calligraphy, he becomes a “conduit”. His words: “My body posture, my breathing, my anchoring, everything is involved and intentional. It requires great physical strength”.

What does it all have to do with the Japanese inspired rope bondage – Kinbaku – we study in our magazine? I’d say a lot! Aren’t these words from Chris so true about the rope bondage as well, isn’t that the mysterious MU – empty mind – we are all chasing in the workshops?

“I prepare the signs. I first choose the characters for their symbolism, then I have to master them to perfection, especially since the large format is not forgiving. I need training. I need to intergrate the sign deep within me to release the energies without my mind disturbing my body on the trajectory of the line of the ink”.

I was touched by the depth and humbleness in all of those craftsmen serving the world with their gift. It seems to me, it does not take much to be creative.

Creation, however, requires both excellence and humbleness.

Some beautiful words at the end from Dadan Horton: “Actually, I’m not creating that much. What I do is a reproduction of history and tradition. My artistic part only goes to the aesthetical part. Not adding the elements. Like in furniture making. If someone is asking for a chair, you do a chair. You can do a possibly beautiful chair, but it’s a chair. It’s a seat with four legs. This is what I mean with handcraft”.

I found some great answers for myself in this research on cratfsmanship.

I would like to end this series for now, but before I move on, there is one more interview I want to present for your attention. Fashion craft. The ultra high craft of forming the body whilst respecting their individuality. Ladies and gentlemens, the tailor made corsets!!!